The Benin Bronze's are glorious

Stunning masterpieces of the great Benin Empire (located in present day Nigeria – not the country of Benin), they represent one of the world's finest traditions of metal work. The Bronzes are important not only because they are artistic masterpieces, but because they challenged scholarly presumptions about African metal work; the director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor said "it was a "revelation" ...that refined metal work such as this had been made in 16th Century Africa." (1)

Head of an Oba, 16th century (Metropolitan Museum)

The Benin Bronzes come from a highly specialized ancestral tradition of bronze casting; a practise which began well before the 12th century. Bronze work was a hereditary occupation, passed down from father to son; it is uncertain what role women played in the craft. Metal art was made through the process of lost-wax casting, using fine clay in place of plaster to form the moulds. These artisans were adept at casting copper and bronze in the same piece, a remarkable feat given the difference of respective melting temperatures.

Bronze casters in the Benin Empire enjoyed a high social status; a later Oba (ruler of the Benin) "so valued the importance of art as a tool of governance that he raised the head of the royal casting guild to the level of privy counsellor within the court hierarchy."(2) Members of the Bronze Casting guild were only allowed to create pieces for the Oba, transgressors of this law risked the death penalty.

The Bronzes held an important role in Benin culture. Lacking a writing system, in order to commemorate and remember important events, the Oba commissioned the bronze casters to make a record of them in bronze. For instance, the first project of a new Oba was to commission a bronze head of the previous Oba. There is interesting linguistic evidence pointing to the importance of these artifacts; in the indigenous language of the Benin Empire, Edo, "the verb sa-e-y-ama means ‘to remember’, but its literal translation is ‘to cast a motif in bronze’. At the court of Benin, art in bronze perpetuates memory...."(3)(4)

Plaque, warrior and attendants, 16h-17th century, Edu People

With the British Museum in London holding the most valuable collection, more than 1000 bronzes are kept by museums across Europe and in North America. Most of the Bronzes were taken in 1897 after the punitive Benin Expedition; when the British "captured, burned, and looted Benin City a bringing to an end the west African Kingdom of Benin."(5)

Nigerian governments have sought their return since the country gained independence in 1960. In late 2018 interested parties decided to "conditionally repatriate" some of the bronzes pending the building of a museum in Nigeria. It will house Benin Bronzes on rotating loan from the "Encyclopaedic Museums" that presently keep them (such as the British Museum).

Queen India, 16th century (British Museum)

Ellen Otzen, “The mad who returned his grandfather’s looted art”, BBC World Service, 26 February 2015

Kathryn Wysocki Gunsch, “The Benin Bronzes are not just virtuoso works of art – they record the kindgom’s history, Apollo magazine, 22 November 2018

Ibid.

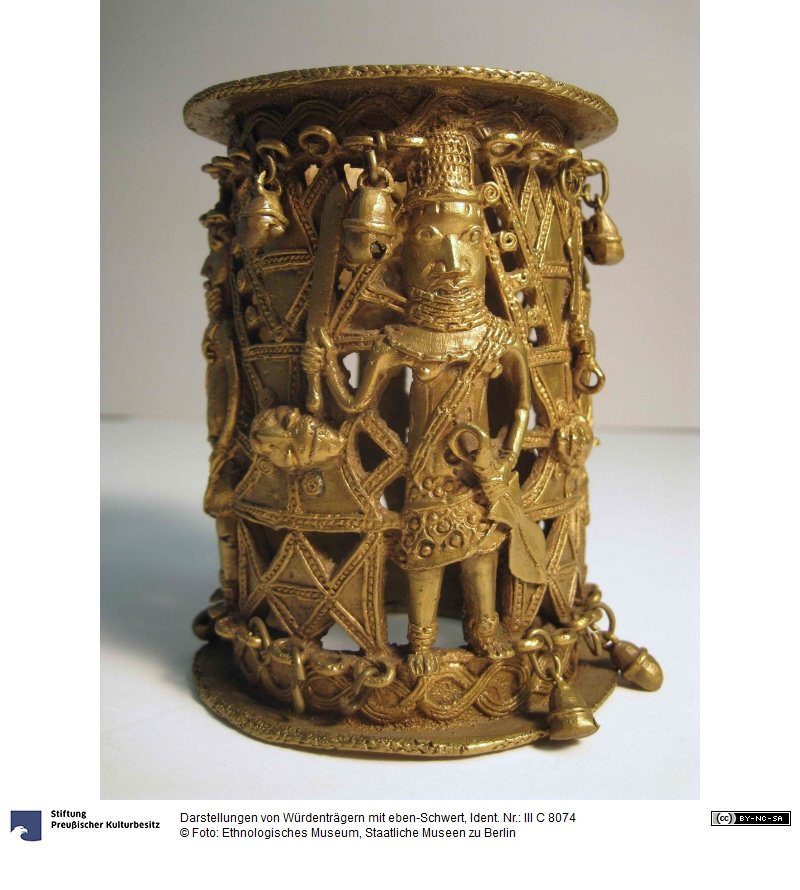

The Bronze casters also made jewellery, such as the piece below from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Wikipedia entry for “Benin Expedition of 1897”

This is the bronze of Queen Idia who “played an instrumental role in her son's successful military campaigns against neighbouring tribes and factions [in the early 16thcentury]. After her death, Oba Esigie ordered dedicatory heads of the queen to be made, to be placed in front of altars or in the Queen Mother's palace. The heads were designed to honour her military achievements and ceremonial power”. Wikipedia entry for Bronze head of Queen Idia.

Image for reference 4

The Bronze casters also made jewellery such as this piece from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin